Diesel vs Gasoline Refining: What Are the Difference?

While diesel fuel and gasoline come from the same source—crude oil—they are processed at a refinery in very different ways. These differences impact everything from the environmental performance of diesel and petrol and fuel prices to refinery margins and even the long-term energy policy of a country.

This article clearly and in a balanced manner explains diesel refining and petrol refining and outlines the evidence and the various factors – technical, environmental, and economic – that influence the diesel vs petrol refining world.

What Is Diesel Refining?

Diesel refining commences in the atmospheric distillation unit (ADU), where we apply heat to crude oil so we can separate it into its various components based on their boiling points. Of varying mid-distillates that we can extract, we can collect Diesel fuel, which is within the boiling point of 200 °C to 350 °C. Because Diesel fuel contains sulfur and heavier hydrocarbons, it has to go through a catalytic process. The process will lower the sulphur levels, which is an industry standard to ultra-low sulphur Diesel (ULSD), which is in most markets today.

Some of the most important technical features of Diesel fuel refining are and include the following:

- Cracking Preservation: Because Diesel fuel is primarily a straight-run product, and refiners are more focused on the preservation of the molecular chains, less cracking occurs.

- High-Pressure Hydrogen Treatment: Intensive treatment is needed because of the industry standard of ultra-low sulphur Diesel (ULSD).

- No High Octane Requirement: The fuel in the absorption ignition engine needs to have a higher Cetane rating instead of an Octane rating.

Diesel fuel refining therefore can be considered easier than petrol fuel refining, although it can still be an expensive and tedious task, especially in the process of desulphurisation.

What Is Gasoline Refining?

Because there are more standards to meet for gasoline, and because there are slightly more niche requirements for petrol, petrol refining is more complex. Firstly, to meet the requirements of several niche standards, petrol must address requirements related to emissions, octane levels, and performance.

In distillation, gasoline is first pulled out from the light fractions. However, market demand and octane levels should not be forgotten at this point, as demand is high and the octane levels must meet a minimum requirement. At this point, refineries have to utilise deeper processing technologies, for instance:

- Fluid Catalytic Cracking (FCC): high-octane lighter molecules at a greater rate.

- Catalytic Reforming: Naphtha with low octane can be upgraded to a higher octane rating with more aromatics that can be converted to reformate.

- Alkylation & Isomerisation: create additives to improve the combustion of petrol that is cleaner by providing more octane.

- Blending: To satisfy performance and other environmental regulations, additives are mixed in.

Gasoline refining requires more conversion processes, which is also why producing petrol is more sensitive to the quality of the crude being used.

Diesel vs Gasoline Refining: Key Technical Differences Explained

Even though petrol and diesel come from the same type of crude oil, the engineering routes of diesel refining and petrol refining are entirely different. Differences of these types come from molecular structure, desired fuel specifications, and regulatory needs—and these differences dictate how fuel refineries design their process flows.

From the standpoint of diesel petrol refining, diesel is a heavier middle distillate product, so refiners try to focus on keeping the long-chain hydrocarbons and removing sulphur. Gasoline, on the contrary, contains high octane and low volatility levels, which makes it a more complex conversion process requiring catalytic cracking, reforming, and alkylation. These different practices fuel the bottom line and also affect emissions released and the economics of the overall fuel.

The following table provides a summary of the differences in diesel and petrol refining to make these differences more understandable.

| Category | Diesel Refining | Gasoline Refining |

| Primary Distillation Range | Middle distillates (200–350°C) | Light distillates (30–200°C) |

| Process Complexity | Moderate—mainly hydrotreating | High—FCC, reforming, alkylation, isomerization |

| Main Objective | Remove sulfur, preserve long-chain hydrocarbons | Increase octane, create clean-burning light hydrocarbons |

| Key Processing Units | Hydrotreaters, diesel desulfurization units | FCC, catalytic reformers, alkylation units |

| Hydrogen Demand | High (for ULSD desulfurization) | Moderate (mostly in reforming and hydrotreating) |

| Energy Consumption | Driven by high-pressure hydrotreating | Driven by cracking and reforming reactions |

| Product Flexibility | Limited—largely dependent on crude quality | High—refineries can increase gasoline yield via cracking |

| Fuel Property Focus | Cetane number, density, lubricity | Octane rating, volatility, vapor pressure |

| Impact on Refinery Margins | Sensitive to industrial and transport demand | Highly seasonal; influenced by driving patterns |

Emissions from Diesel Refining vs Gasoline Refining

Another important difference between diesel and gasoline refining is in the environmental impact of each, since both pathways emit at different stages and intensities. Though both are energy-intensive operations, the sources and types of resulting emissions depend upon specific refining technologies needed for each fuel.

1. Emissions Associated with Diesel Refining

The production of diesel uses a hydrotreating process, which aims at eliminating sulfur along with other impurities. This process is characterized by high pressure, high temperature, and high hydrogen consumption. Consequently, diesel refining has a large share of its emissions from:

- Hydrogen is usually produced by steam methane reforming, which also produces CO₂.

- Fuel combustion is required to sustain high reactor temperatures.

- Energy use linked to ultra-low sulfur diesel (ULSD) standards

Although diesel refining has fewer conversion steps compared to gasoline, it has an intensive desulfurization process, which makes hydrogen demand and thus CO₂ emissions a notable factor in its overall environmental footprint.

2. Emissions Associated with Gasoline Refining

Gasoline refining entails deep molecular transformation. Units like FCC (Fluidized Catalytic Cracking) and catalytic reforming operate at high temperatures, generating both direct and indirect emissions, including:

- CO₂ and NOx from fuel combustion within FCC regenerators

- Aromatics and light hydrocarbons that must be strictly controlled to meet air-quality regulations

- Hydrogen consumption in hydrotreating, although generally less than diesel

- Higher process heat demand due to the number of conversion units

Because gasoline requires extensive cracking and reforming to achieve high octane levels, the refining chain typically has a larger carbon footprint per liter of finished product.

Wider Environmental Context

On a process level, CO₂ emissions from refining gasolinel tend to be worse due to the energy-intensive cracking and reforming processes. Diesel refining, as a simpler conversion, depends more on hydrogen production. This also involves emissions unless low-carbon hydrogen is used.

When taking full lifecycle emissions into account (refining + combustion in engines), the comparison shifts again. Diesel engines are more efficient, but historically produced more NOx and particulates, while gasoline emissions are more CO₂ due to being less efficient. This is more the case with modern emission-control technologies, and they continue to close the gap.

Which Is More Expensive to Refine, Diesel or Gasoline?

The cost of refining diesel and gasoline depends on many factors: crude quality, refinery configuration, and various regulatory requirements. Generally speaking, gasoline refining is more complicated because of the high degree of conversion required to reach high octane, while diesel refining is dominated by hydrotreating for sulfur removal. The table below summarizes the main cost drivers for each fuel.

| Factor | Diesel Refining | Gasoline Refining |

| Primary Processes | Hydrotreating (HDS), mild hydrocracking | FCC, catalytic reforming, alkylation, isomerization |

| Energy Consumption | Moderate — mainly for hydrogen production and high-pressure reactors | High — multiple conversion units operating at high temperature |

| Capital Costs | Lower — simpler unit configuration | Higher — complex units and multiple catalysts required |

| Regulatory Impact | ULSD standards increase hydrogen and energy demand | Seasonal octane and emissions standards add blending complexity |

| Flexibility | Limited — diesel yield tied to crude composition | Higher — gasoline production can be adjusted via cracking and reforming |

| Overall Refining Cost | Moderate | Higher |

Although diesel refining requires more hydrogen and energy for desulfurization, the refining of gasoline requires several energy-intensive conversion processes with capital-intensive units. Producing high-quality gasoline is generally more expensive per liter compared to diesel; the exact difference would depend on the setup and crude slate at the refinery.

Conclusion

Diesel and gasoline both come from crude oil, but need to be refined differently. For diesel, the sulphur needs to be removed and the middle distillate quality is maintained. For petrol, the refining requires multiple processes to achieve the desired octane and be environmentally safe. These differences impact the refining costs, energy consumption, emissions, and the overall availability of the fuel and fuel price.

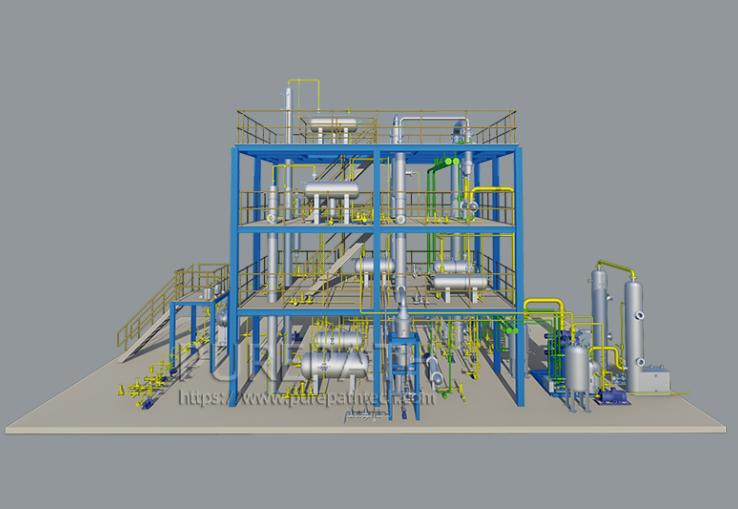

Having an updated oil refinery is essential for producers. Updated petroleum refining equipment provides system control for reactions such as hydrotreating, cracking and reforming, and streamlining the production of diesel and gasoline. Beyond being efficient, self-regulating systems reduce emissions and environmental risk, and are therefore an essential investment for any refinery looking to be competitive in the current fuel market.